I wrote the following for Megaphone News on Global Voices (link soon). You can watch the Megaphone video (Arabic with English subtitles) it was based on above. If the video doesn’t appear in your browser, click here.

In recent months, the Lebanese government, and in particular its foreign minister and head of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) Gebran Bassil, have been pushing for a return of Syrian refugees to Syria.

Striking a ‘populist’ and xenophobic tone increasingly common throughout the world, the FPM even launched a “central committee for the return of refugees” while accusing refugees of posing “a threat to Lebanon’s identity and economy”.

Oddly enough, this came at around the same time when Bassil, who said that “there is only one road for Syrians, and that is the road home”, supported the naturalization of hundreds of mostly Syrian businessmen.

The FPM and its supporters have been arguing that many parts of Syria are becoming ‘safe’ again given the recent military victories by the Assad regime and its Russian, Iranian and Iran-backed sectarian allies. The latter includes Lebanon’s Hezbollah party, an ally of the FPM.

Hezbollah has also opened nine offices in South Lebanon, the Bekaa valley and Beirut’s southern suburb “to help the refugees return to Syria.” Notably, Hezbollah’s operations involves having refugees fill out an application which is then sent directly to the Syrian regime for approval.

Meanwhile, in the south of Syria, in just a few weeks starting mid-June, between 270,000 and 330,300 Syrians were forcibly displaced from the rebel-held city of Daraa due to intensive bombing campaigns.

They’ve been making their way to the Israeli-occupied Syrian Golan Heights and, especially, the Jordanian border. At the time of writing, both governments of Jordan and Israel continue to prevent refugees from reaching relative safety.

Read: Jordanians lend a hand to displaced Syrians despite the government’s insistence on closed borders

This latest offensive follows a similar patterns of intensive bombardments and large-scale displacement already seen in formerly rebel-held areas of Syria such as Eastern Ghouta, Aleppo, Daraya, Homs and other places.

But the dangerous security situation in Syria has not stopped many Lebanese politicians from resorting to the now-common fearmongering and scapegoating.

In a December 2017 article, Global Voices contributor Elias Abou Jaoudeh and I argued that with the Lebanese government failing to tackle most structural problems in the country, diverting focus away towards Syrian refugees has become all-too-easy across Lebanese society.

To quote from the piece:

Despite the verified facts of Syrian refugees’ struggles in Lebanon, official scapegoating, regularly aided by mainstream media outlets, have led to the spread of anti-refugee rhetoric across Lebanon and this tension has escalated over time.

This was followed by another article comparing the scapegoating tactics against Syrian refugees with the much older ones directed at Palestinian refugees in the country.

Pushing for refugees’ return regardless of consequences

Bassil has launched attacks on the UN, accusing it of “scaring refugees” from considering returning to Syria.

This was followed by reports that the UNCHR, the UN’s refugee agency, will ‘encourage’ refugees’ return under pressure by the Lebanese government which freezed the agency’s staff residency applications on June 8.

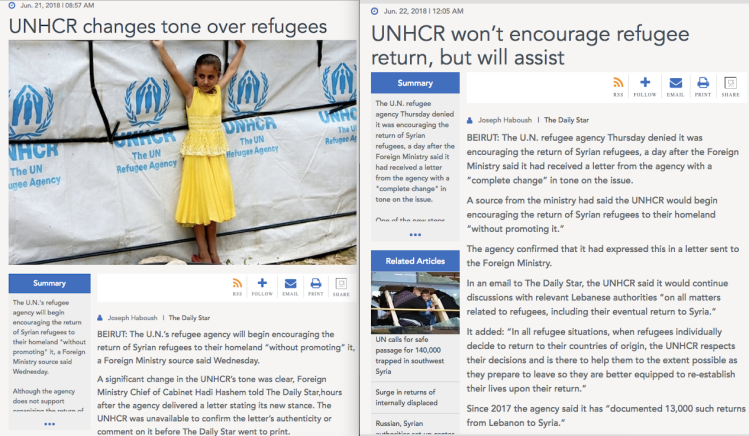

The UNHCR later denied these reports. This can be exemplified by comparing these two headlines by the Lebanese anglophone ‘The Daily Star’ on June 21 and June 22.

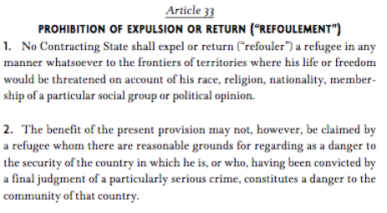

While many have pointed out that the UN has no legal right to ‘encourage’ refugees to return to a war-torn country – it is, in fact, a violation of Article 33 of the Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees – what is not often discussed is why Bassil chose to target the UN instead of his allies in Syria, the Assad regime.

On April 2, 2018, the Syrian regime passed “Law No. 10“, which “allows for creating redevelopment zones across Syria that will be designated for reconstruction”.

The situation has gotten so desperate that Palestinians have compared Law No. 10 with laws passed by the State of Israel since 1948 designed to prevent Palestinians from returning to their homes following the mass ethnic cleansing referred to in Arabic as the ‘Nakba’, during which over 700,000 Palestinians were driven from their homes by Zionist forces.

Human rights groups and activists have since been raising the alarm as they view it as the regime’s attempt to prevent refugees from returning.

As Human Rights Watch (HRW) explained:

The law does not set out any criteria for which areas can be designated as redevelopment zones or a timeline. Instead, redevelopment zones are to be designated by decree. Within one week after a decree is issued, local authorities are to request a list of property owners from the area’s public real estate authorities. Public real estate authorities must provide the lists within 45 days.

Adding:

If their property does not appear on the list, people who own property in the zone are to be notified and have 30 days to provide proof of ownership. If they fail to do so, they will not be compensated, and ownership reverts to the province, town, or city where the property is located. Those who succeed in proving property ownership will get shares in the zone.

Even Bassil seemed to have been taken by surprise as he sent a request for explanation to the Assad regime and asked them to ‘revise the law’.

Given that the security situation is far from ameliorating, and that many refugees fear reprisal or forced conscription into the Syrian army, this effectively means that many refugees would not be able to provide proof of ownership, thereby losing the legal right to their own homes.

This would in turn pave way for the regime to ‘redevelop’ the land.

It is worth noting here that Law No. 10 has some precedence in Decree 66 of 2012 which established, among other things, the planned creation of ‘Marota City’.

Investments for Marota City, while formally coming from the state-owned Commercial Bank of Syria, are widely believed to include regime-linked billionaires such as Rami Makhlouf, Assad’s cousin “who hails from the same family as the minister of local administration and is known to sponsor loyalist militias“, and a wealthy Kuwait-based Syrian investor named Mazen Tarazi. Future landlords include Syrian-Turkish-Lebanese businessman Samer Foz.

And while the regime advertises this project as affordable, Aron Lund noted for IRIN News that the reality is quite different:

Syrian authorities present the Decree 66 redevelopment projects as an unmitigated success story, but even pro-government media has noted the absence of alternative housing for people evicted from Basatin al-Razi [where Marota City is being built]. Former residents were recently told they may get new apartments in the coming three years.

So, six years later, with the arrival of Law No. 10, many Syrians displaced by the war have added ‘redevelopment’ to a long list of reasons why return may well be impossible.

This is especially true as over 70% of Syrian refugees in Lebanon come from the devastated areas of Aleppo, Homs, Idlib and Rural Damascus.

And this is in addition to reports of returning refugees being forcibly conscripted into the army and some even tortured and killed.

To quote one refugee interviewed by Maha Yahya for the BBC:

Hassan, an unregistered young refugee living in Beirut, put it: “Today, everyone who leaves Syria is considered a traitor.”

Like many others, he fears being accused of deserting his country and the possibility of reprisals.

Adding:

Young men in particular are concerned that they will be targeted by forced conscription into the army.

Several recounted stories of young men who had returned to Syria only to get drafted and die at the front.

The cost of avoiding conscription can go up to $8,000, meaning that most Syrian men who fled the country would be forced to join the army if they return.

If refugees in Lebanon are forced to follow similar patterns, tales of horror will likely continue well into future. As Saskia Bass wrote in March 2018:

New research among returnees shows that most were pushed home by the harsh living conditions in neighboring countries, and did not find safety or dignity upon return.

If you support the content published on Hummus For Thought, please consider donating $1 per month on Patreon to help the site become self-sufficient.

I’d just like to draw your attention to Irish Syria Solidauity Movement’s petition to Leo Varadkar: https://my.uplift.ie/petitions/use-irish-peacekeeping-record-in-lebanon-to-protect-syrian-civilians-from-deportation